How to launch a tech product in a large company

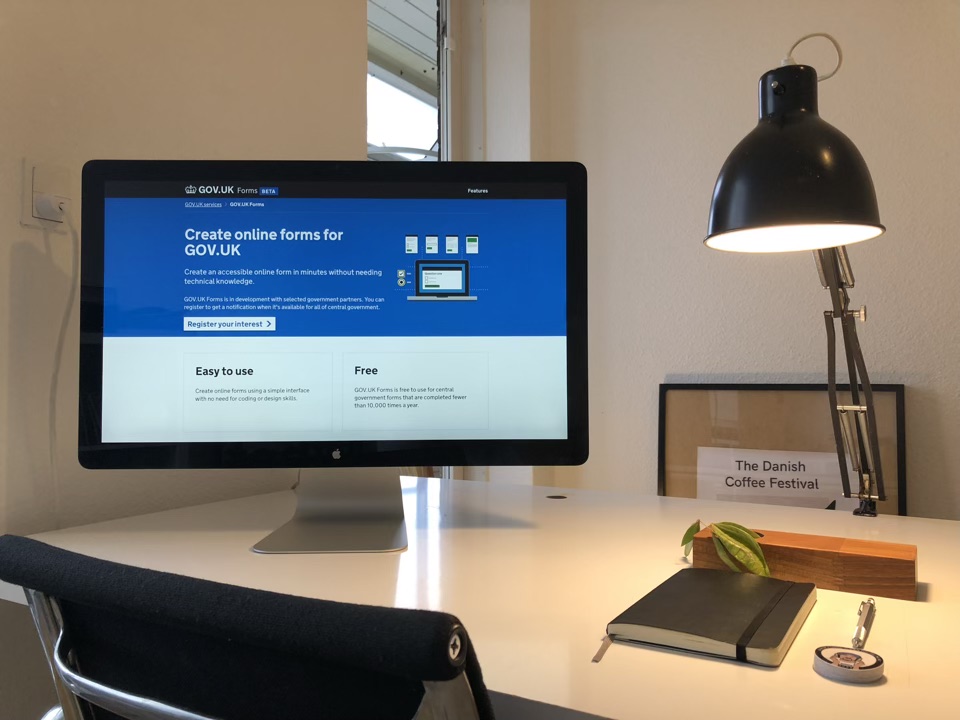

Last month, our first customer launched their first online form with GOV.UK Forms. GOV․UK Forms is a new product. It makes it easy to create accessible online forms for the UK government website, GOV․UK. without needing any technical knowledge. After two years of product challenges, I’m sharing four of my top tips.

I’m hoping this post will be especially useful for:

- people working in large companies with less experience in launching tech products

- people curious about product management

- people trying to find out what it means to put customers at the centre

While there’s a bit less in here for people already working in tech, let me know if you folks found anything useful.

1. Find someone with just enough budget who cares

When you’re starting out, you don’t need much internal investment. You only need someone with some budget to fund two or three people for anything from six weeks to a few months. This team might include a product manager, a designer or researcher.

I was looking for an opportunity to move onto something new in our company. I heard our Head of Product might have some budget for exploration into new products. I had worked for stints on products at all scales, but I wanted to see a product through from start to launch.

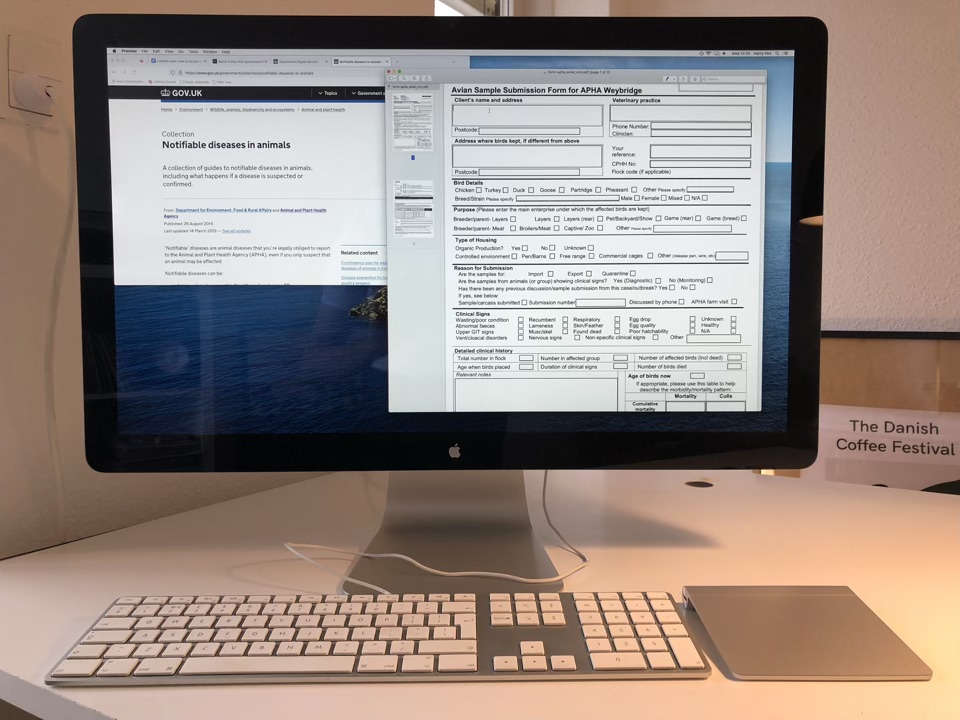

They were curious about a few different problems, but one stood out to me. It was more tangible than the others: government has many good digital services. Yet lots of teams were still using PDF forms. These are hard to use, slow to process and have accessibility issues.

I persuaded them to let me use some leftovers from another budget. I could spend up to three months exploring the problems with whoever we could get hold of at short notice.

2. Do just enough research to see if there’s a problem that your company is well-positioned to solve

In a large company, it can be tough to know how much research is enough before you experiment with new products.

It’s not one or the other; research or building products. Not if you use a continuous discovery approach. Though with a new product, I’d usually hold off experimenting with building things. Instead, start with some timeboxed research. This helps to understand the problem a bit better. It focuses your product experiments. The question is, how much research is enough?

Large companies don’t usually have as tough capacity constraints. In a startup, you have to prioritise only the most important research. However, just because you have more capacity to spend more time on research, in most cases, I don’t think you should.

Photo: Some rights reserved by gdsteam.

Unlike startups, larger companies are usually quite harsh places to launch new products. Organisational inertia will work against you. I believe you have to quickly weigh up two things:

- The value of doing more research before starting to experiment with new products

- The risk of someone moving you back onto teams that have already proven their value

The way to reduce this risk is to do some initial research to understand the problem. Then quickly move to showing the value of your new product experiments.

We did some initial research to understand the problems with PDF forms. We wanted to get to the root causes of these problems. After six weeks, I could make a recommendation about whether to explore any further. The research had given me what I needed:

- We knew enough about customers’ problems

- We knew how well positioned our business would be to solve those problems

We knew customers weren’t able to create good forms because:

- there’s a poor return on investment in digital teams for most smaller services. The majority of government forms support smaller services

- existing online form builders had problems with accessibility, ease of use or high costs

As a result, most teams ended up using PDF forms. These are generally slow to process, hard to use and have accessibility issues.

Let's look at our business' positioning. "We build platforms, products and services that help deliver a simple, joined-up and personalised experience of government to everyone." Solving problems with forms would simplify the experience of government. So there was a clear reason for our business to invest in this area.

Our business had a good track record of building platforms and products. Other government organisations use them to serve the public. We were well-positioned to solve these problems with forms.

Finally, we had a strong business case for investment. We estimated we could save around 8 minutes each time someone processes a form.

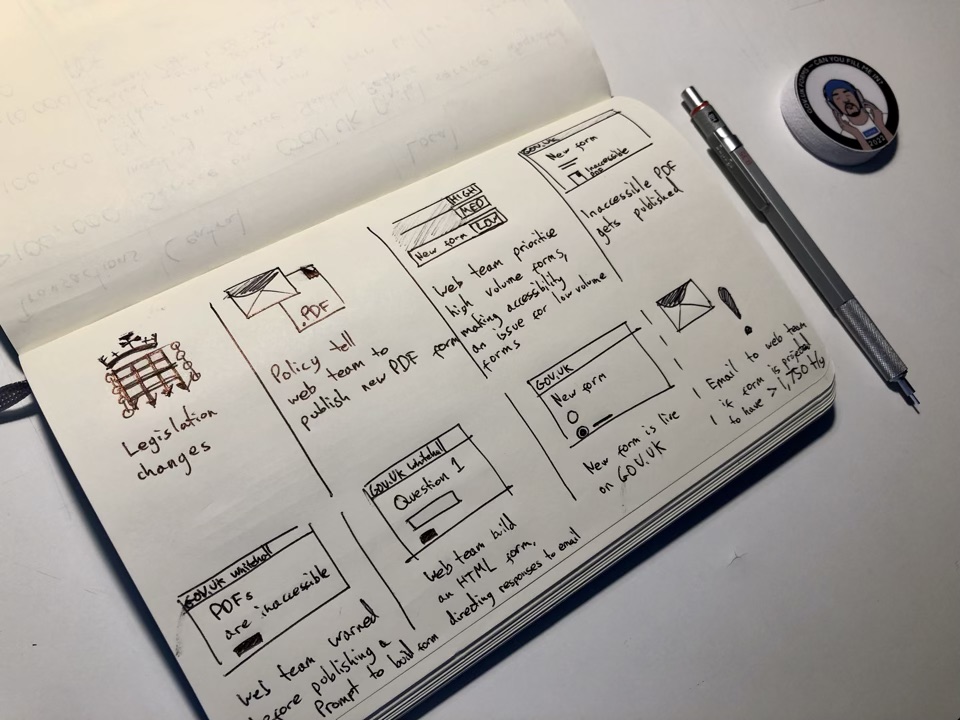

After those first six weeks, I started sketching ideas for initial experiments. I don’t think you need to have loads of ideas at this point. Though it helped to point at some sketches and say, “I need a few more people in the team to help test this out.”

Sometimes, after six weeks, you might feel you don’t know enough about customers’ problems. You might not be able to make a strong recommendation. This is okay if you’re working in a complex area. You’ll benefit from a bit more time. Other times, it’s a sign that you or your colleagues are looking for too much confidence early on. You don’t have to have answers to all the questions, only the most important ones. There’s always time to answer less important questions in later experiments.

Sometimes, after six weeks, you might feel you don’t know enough about your positioning. This can be quite difficult to judge. Especially because you’ll only ever know so much about what will happen in the market. It can be tempting to guess at specific product launches from other companies. Though at such an early stage, you’re usually better off evaluating your own company. Some important questions might include:

- if you solve these customers’ problems, how will your company get closer to its vision?

- what impact might you have on high level metrics? e.g. CO2 emissions, social impact, growth, customer engagement, revenue, loyalty or operational costs

- what level of support and investment might you need to tackle these problems?

- how strong are your relationships with your ideal customers?

- how quickly can you build a team?

3. Build a team to test riskiest assumptions

You’ve found problems your company is well-positioned to solve. Now you need more people in your team to help you develop experiments and new ideas. Then you can test how effective they are at solving your customers’ problems.

If you don’t already have a designer in your team, you definitely need one at this point. I think most of the other roles depend on what experiments you might want to run. It’s also dependent on how specialised people are. You’ll need someone to manage the product. Though that doesn’t necessarily mean having a product manager at this stage. If the skills are there, you could have others in the team managing the product. When launching a tech product, you’ll generally want a technologist in the team. That could be an engineer, technical architect or data specialist. Again, it depends on the experiments.

You might get lucky, but you should expect to struggle with the blend of roles and skills in the team. In a growing company, you can improve this by moving people in and out of the team. However, in a static or shrinking company, you can end up with a shortage of some skills and a surplus of others. It’s always hard to know exactly what skills you’ll need for experiments, many of which you don’t yet know you need to test.

Before you get carried away with building a product, you need to understand what the product might need to do. How will it solve the customers’ problems? In my experience, it's useful to test your riskiest assumptions. Doing this helps you to focus on experiments that really matter to the success of your product.

Before we started building GOV․UK Forms, we tested our riskiest assumptions, such as:

- can we make it easy to create better forms?

- can we make it cost-effective for smaller teams?

- can we convince decision-makers to adopt our platform?

We tested these assumptions by:

- testing different prototypes with customers to see if it was easy to create forms

- checking the quality of the forms customers were making with different prototypes

- exploring different business models and testing pricing with customers

- testing marketing sites with different propositions with customers

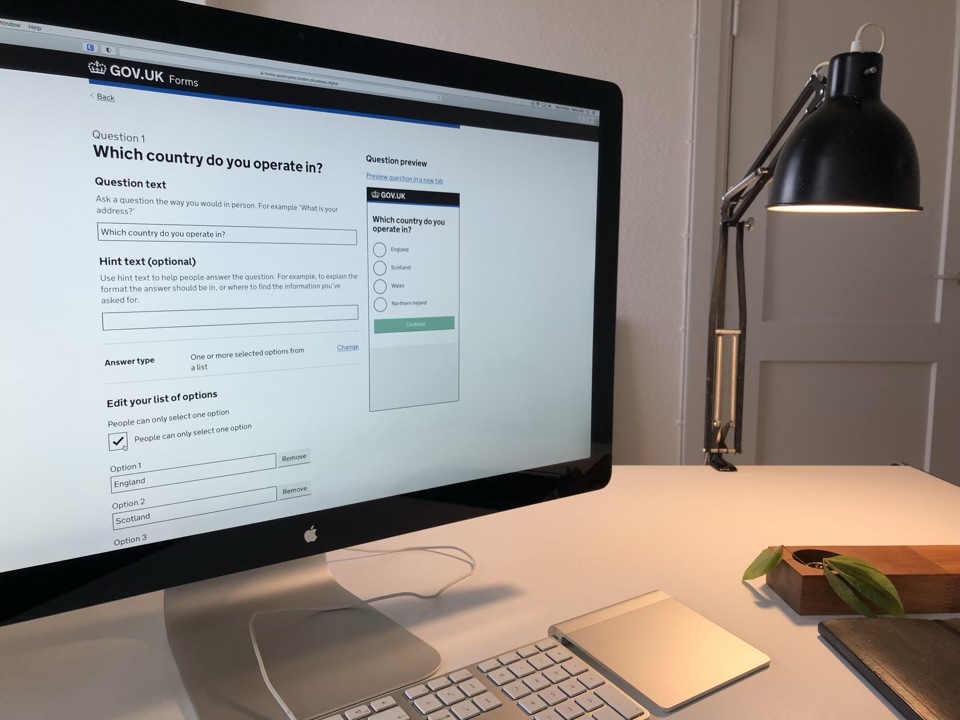

These experiments often surprised us. For example, our customers aren't from a design or tech background. I thought they would struggle to create better forms. Most of them created pretty good forms. Though it wasn’t clear when they needed to use radio buttons versus checkboxes. Once we started building our product, we removed the need for customers to understand technical terms.

You've used prototypes to test your riskiest assumptions. Now you can now start building a real product.

4. Build a super simple product to launch with a few customers

At this stage, you might not know exactly how every bit of your product will work. Though you should know how the fundamental interactions will work for your customers. To support a quick launch, you’ll want to bring more engineers into your team.

With GOV․UK Forms, we started building the simplest possible way to create a form, send a form and receive a form. The process of doing this started to tease out choices. Things like our programming language, cloud infrastructure and our deployment pipeline. Importantly, we were able to start testing the actual product with customers.

Last month, our product launched successfully without things that I had before thought of as essential. I wish I had realised it sooner, but it has to be scarily simple to start off with. It was painful to deprioritise things I felt were valuable. Things I saw as valuable to our customers, and in our business-to-business (B2B) context, their customers.

As a product manager, I was responsible for the quality of the product. So I really wanted to provide a good product. Though I had to balance the quality of the product with delivering something at a useful moment for our first customers. Also, I didn't want to make stakeholders wait too long to celebrate a launch.

Although it was scary, I told our first customers we’re not going to have certain features until a later launch. We were fortunate that they were so understanding. Keeping it simple helped our team focus on the first launch. In the end, we actually delivered all the deprioritised features just two weeks later.

Share your tips

To help me write better posts, I’d love to get your feedback. If you found this useful, please repost to share it with your network.

To help me and others learn more, it would be great to hear your experiences of launching a tech product in a large business. They can be both good and bad. Please share your tips.

Photo on screen: Some rights reserved by Jorge Franganillo.

I’ve recently moved to Copenhagen, Denmark. I'm looking for my next product management role with opportunities for social or environmental impact. If you’re interested, please connect and let’s get kaffe!

Next: Prioritise the riskiest assumptions in big problem spaces

Previous: Good services can support bad policies, and bad services can support good policies. It's messy